Carbon farming is like taking on a new crop or breeding a new line of sheep. It is a business decision with costs and benefits. It has the potential to add to a farm enterprise, to provide a new source of revenue and to contribute to the sustainability and profitability of the farming operation. However, it also has risks, uncertainties and, importantly, a number of regulatory, compliance, reporting and auditing requirements.

Like any business decision, the choice to participate in the ERF involves understanding and a careful comparison of the benefits and costs. Note that the benefits and costs will be constrained (and in some cases mostly determined) by the regulatory and policy environment within which the carbon farming business will operate.

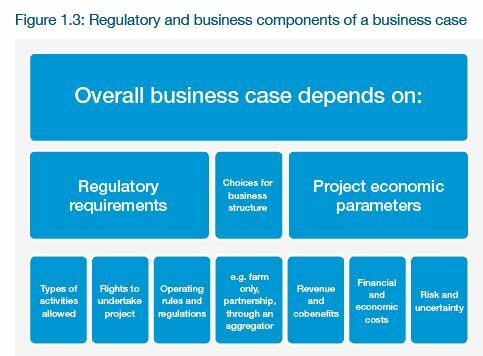

Thus, the business case for carbon farming involves both regulatory components and business components (Figure 1.3). The components are closely related: the business cannot proceed unless it meets the regulations, and the regulatory environment will in part determine both the business costs and the revenues that can be earned.

Each of these elements of the business case is considered in this manual, although the greatest emphasis is on the farm economic components. Once it is clear that the business can meet the regulatory requirements, and a business structure has been chosen, the remainder of the decision depends on farm economics: is the proposed business viable, what returns will it generate and what are the risks?

As this manual shows, relatively straightforward calculations can be used to determine some of the key economic parameters underlying carbon farming projects. Carefully projecting those elements will provide a strong indication of the potential value of a carbon farming project and thus whether it is worth pursuing the project in more detail.

The financial case is just one part of the broad economic viability explored in this manual. Because the ERF may involve co-benefits that have potential implicit values to the farm (that is, values that are not necessarily monetised), or because the farmer may have nonfinancial reasons for pursuing sustainability, the key decision is an economic one. Where there are no co-benefits (or where benefits are all explicitly financial), the economic case becomes a financial case. There are a number of models for participation in the ERF.

Essentially, the farmer can run their own project or form various types of commercial partnerships with other farms or specialist carbon farming organisations. Some of those organisations are known as aggregators, and are likely to be a crucial part of participation in the ERF.

|

|

Explore the full Workshop Manual: The business case for carbon farming: improving your farm’s sustainability (January 2021)

Read the report

RESEARCH REPORTS

1. Introduction: background to the business case

This chapter lays out the basic background and groundwork of the manual

RESEARCH REPORTS

1.2 Being clear about the reasons for participating

Introduction: background to the business case

RESEARCH REPORTS

1.4 Working through the business case for carbon farming

Introduction: background to the business case

RESEARCH REPORTS

1.5 Factors determining project economics

Introduction: background to the business case

RESEARCH REPORTS

1.8 Important features of the business case

Introduction: background to the business case

RESEARCH REPORTS

2. How carbon is farmed under the ERF

This chapter considers in detail the activities that constitute carbon farming

RESEARCH REPORTS

2.5 Carbon farming under the Emissions Reduction Fund

How carbon is farmed under the ERF

RESEARCH REPORTS

3. The policy context and the price of ACCUs

This chapter takes a broad look at the policy context for carbon farming